Synopsis of Sites

01 Scouting the Yamhill Rivers

(There are few put in and take out points on the Yamhill Rivers open to the public and the rivers are notoriously hazardous for inflatable craft, with snags, log jams and bank slumps to contend with. The rivers meander to such an extent that floats of a few linear miles will take all day. Know what you are doing before attempting these floats!)

During approximately eight to ten weeks of late summer, the Yamhill Rivers drop to acceptable levels to scout for new sites and search the river banks and bottom for fossils. With patience, a keen eye and a basic understanding of the geology at work in the river system, the persistent explorer can be rewarded with a fossil find from the late Pleistocene. The most common are flood washed shards of bone from two of the largest of the mega-fauna: mammoth and bison; but also in evidence are the fossilized remains of the giant ground sloth, mastodon, horse and camel.

Nearly all of the fossils found while scouting have been washed out of the bank, and down the river. They are found while floating or wading downs the river, walking the banks, or when an area looks promising and has produced repeated finds, snorkeling or SCUBA gear is used to survey the bottom of the river.

While beautiful and identifiable specimens continue to surface, the majority of the bones found are fragmented, show extensive stream wear, and are not taxonomically identifiable. But even the smallest and most inconsequential fragments are plotted on a map and help show dispersion fans that aid in pinpointing more important finds.

Only rarely are in situ remains found and these come in two general categories: those associated with the catastrophic flood deposits which were laid down at the end of the Pleistocene and remains which are relatively untouched by geologic action after initial deposition. In situ flood specimens are generally scattered and usually fragmentary, often showing green bone type fractures and desiccation. They occur in the poorly sorted Missoula Flood deposits which are in evidence in many of the cut banks of the river, and form the scoured river bottom or intrusive dikes in places along the river course. In situ finds which have remained relatively undisturbed by geologic processes since initial deposition of course remain the most exciting but elusive of finds. Preservation of these fossils can be quite exquisite, with the most minute of details clearly visible. Predation and scavenging marks are visible on many, along with green bone breaks, scarring, un-fused epiphyses, and other taphonomic indicators which allow us a rare and detailed look into the conditions of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene of the Yamhill Valley.

River Scouting, the early years 1965 – 2000 Mike Full started grew up on the South Yamhill River rowing his way through boyhood adventures in a small wooden dingey that he bought with money earned mowing lawns. His first fossil, a mammoth tooth, was not even recognized as a fossil for several years, just an interesting rock. A small box of bones were the sum total of his curiosity when he went off to college and later became a police officer back in McMinnville. Curiosity again pulled him to the river and in the summers he found several more bones, carefully logging each one onto a map for future reference. Soon, Marvin Reken joined him and the “Yamhill River Pleistocene Project” was born.

River Scouting, 2000 Computerization caught up with us after finding the McMinnville Mammoth and yearly fossil logs were scheduled to replace the simple “spots on the map”, allowing us to study the river in annual cycles. This gave us a yearly look into where fossils were showing up on the river, allowing us to focus on developing debris fans. Our first debris fan, “SpearPoint” and second one “Ivory Beach” became study focal points.

River Scouting, 2001 The summer of ivory! Numerous pieces of ivory tusk, mostly just shards, littered the beach and river bottom at “Ivory Beach”. Each was charted and logged onto the river maps. These new finds and previous finds in the area show a developing debris fan that abruptly stops, with no fossil fragments being found in the shallows just upstream. If our debris fan model proves out, we will be finding a mastodon wearing out of the bank in this area some time in the future.

River Scouting, 2002 Mike Full was posted overseas with the International Police Task Force, USCIVPOL UNMIK and only had one float before leaving. This yielded a tusk stub and a bison vertebra. Nice way to leave!

River Scouting, 2003 Mike Full returned home from his overseas posting in time for only one river float. It yielded a bison vertebra, a nice homecoming!

River Scouting, 2004 In the most notable find of the summer, Marvin Reken and Christine Hamilton picked up a tooth root of a large mastodon tooth from SpearPoint beach. It was quite a mystery bone for several years, until we sent it to the Page Museum for identification. Mike Full and Dean Gill found the distal end of a large mammoth femur on the gravel river bottom, an impressive looking piece of fossil! Mike went on to find part of a bison mandible with two teeth still in it, and later a large chunk of ivory from the core of a tusk. Not a bad year!

River Scouting, 2005 Small bone and ivory fragments categorized a year when we did not get the time to spend on the river. Few floats were made. Our most diagnostic find was a really nice bison phalange picked up off of the gravel bar at ivory beach.

River Scouting, 2006 The most notable finds of the summer consisted of a juvenile mammoth tooth found by Mike adjacent to a small creek drainage that has yielded several other fossils. We are working to develop a debris fan chart for the area and try to find where the fossils are wearing out from.

Mike also picked up a ten inch long piece of a small mastodon tusk round near where a small mastodon tooth was picked up many years before. We are working on developing another debris fan to determine where these fossils are coming from.

River Scouting, 2007 Oregon Field Guide sent a crew to accompany us on a scuba dive of the South Yamhill river and Mike Full found a huge sloth digit to a Paramylodon harlonii in the channel right off of Ivory Beach!

Mike also found a small humerus while scuba diving off of the McMinnville Bison Site that we could not identify. Thanks to Dr. Alison Stenger’s resources, we got it identified by the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits as a humerus to a bighorn sheep. First fossil of one we have heard of west of the Cascades.

A mammoth tooth and a bison vertebra rounded out a fun summer!

River Scouting, 2008 Variety was the key work for 2008. Scouting the river revealed bison vertebra, part of a bison mandible, a horse tooth, and various ivory and bone shards.

Dr. Lyle Hubbard found a section of tusk from a mastodon, his first ever ivory find….now he is a mastodon hunter!

While scuba diving, Marvin Reken and Lisa Ripps located a mammoth or mastodon pelvis….what a find!

River Scouting, 2009 The cub scouts had a wonderful outing and found two pieces of mega fauna bone on the banks of “ivory beach”. Several bone fragments were picked up from along the river course during the summer; the most fascinating being a bone fragment picked up by Alia Moore has recently been tentatively identified as part of a bison horn core, most probably from Bison antiquus. A couple of mammoth tooth plates and two bison molars rounded out a good summer of fossil hunting.

River Scouting, 2010 Notable finds included mammoth tooth plates; one discovered by Joanie Livermore near the Royer mastodon site and another by Mike. Two bison molars were picked up off of the gravel river bottom as well scattered pieces of tusk ivory and the distal end of a bison femur. On “Ivory Beach” a beaver femur was found by a Educational Recreational Adventures crew member who was working on site preparation.

River Scouting, 2011 Notable finds include a rib from the McMinnville Mammoth discovered by Mike Full and Marvin Reken, protruding from the bank of the South Yamhill River at the downstream edge of the McMinnivlle Mammoth Site. It had been visible for several years, with just the proximal end of the large nearly intact rib barely protruding from the bank, resembling a cobble. Only careful examination revealed what it was to us.

Later in the summer, Mike checked a developing debris fan and found a section of the back of a mastodon skull with part of the foramen magnum visible, protruding from a gravel bar on the bottom of the river.

Rounding out the summer were several shards of ivory, two cervid teeth and a couple of mammoth tooth plates….a good year!

River Scouting, 2012 A year of firsts! Marvin Reken spotted the proximal end of a mammoth tibia/fibula protruding from the gravel over the fossil layer approximately 120 feet downstream from the registration point of the McMinnville Mammoth Site. It represents the first articulated mega fauna bones we have found if it is not actually fused. (Final preparation and preservation will show us whether or not it is fused or two articulated bones). The fossil is possibly from a different mammoth, not the McMinnville Mammoth, but still a great find!

Marvin Reken and Mike Full found a sloth claw, only our second ever, on a river scout which included finding fifteen fossils in a single dive and developing a new debris fan exactly where we expected to find one, further validating our theory of being able to locate eroding fossils by their debris fans.

SCUBA diving, Mike Full and Joanie Livermore found a beautiful bison horn core from a Bison antiquus. Examining it lead to the identification of another fossil, found years before, as a bison horn core, possibly from Bison alaskensis. If so, it will be the first Bison alaskensis documented in Oregon. It comes from a debris fan where several other bison bones have surfaced.

On the same trip, we found an exquisite baby mammoth tooth, only 3.75 inches long. It is in absolutely perfect condition and represents the first true infant tooth from a mammoth that we know of in Oregon, and sheds light on the Yamhill Valley population of mammoths, suggesting they were a resident population, not “just passing through”.

Students from the McMinnville High School located a concreted fossil that had weathered out of the McMinnville Mammoth Site, about two hundred meters downstream from the site. It turned out to be two phalanges to the McMinnville Mammoth, still articulated. First unequivocal pieces of the McMinnville Mammoth found articulated.

Not to be outdone, members of the North American Research Group working the McMinnville Site, took time to cool off on ivory beach and Rose found yet another baby mammoth tooth. Nearly a perfect match to the first one, they represent the upper right and left molars. We are naming the baby mammoth represented by this tooth “Little Rose”.

Marvin Reken and Mike Full, on separate river floats, each found another mammoth tooth, bringing the total for the summer to FOUR mammoth teeth in a single year, our best yet. During Mike’s float, he also found a fused bison tibia/fibula.

SCUBA diving off of the McMinnville Mammoth Site, Marvin Reken found a rib to the McMinnville Mammoth and Mike Full found a piece of a mammoth scapula, not from the McMinnville Mammoth.

On the final float of the season, Mike Full (YRPP) and Richard Kimbell (NARG) found a nice cervid tooth and the proximal end of a scapula from a Harlan’s Ground Sloth Paramylodon harlonii.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

02 McMinnville Mammoth Site

(Refer to scientific papers located in the “Publications” section of the web site for stratigraphic studies, fossil identifications, taxonomic descriptions, and other information of general scientific interest on this site.)

The McMinnville Mammoth Site has been excavated over a number of years by the Yamhill River Pleistocene Project. Research at this site is ongoing, and it is closed to the public without specific reason and permission from the City of McMinnville which controls access to the site.

Discovered in 1991 by Mike Full, the McMinnville Mammoth Site contains the disarticulated remains of a small adult, probably female Columbian mammoth, (Mammuthus columbi). The remains were located on a section of the South Yamhill River undergoing active erosional processes. The intact left tusk laying in the water at the foot of a vertical cut bank, and five more fossilized bones were observed protruding from the bank, to include both scapula, two ribs and a left tusk socket.

The find was immediately reported to Dr. William Orr, curator of the Condon Museum at the University of Oregon and Dr. Orr sent Roberty Linder to assess the site and confirm ancient fossil elephant remains.

1991 – 1997 Summer Digs…..First efforts and a huge learning curve Due to the ongoing erosional process and the danger of losing the fossils to floods or bank slump, a hasty dig was initiated immediately to extract visible fossils and assess the extent of the remains. Registration points were established, and a meter grid pattern initiated to plot all fossil remains recovered. Initial indications were that a substantial portion of the fossils remains might still be in-situ at the location.

These initial excavations were carried out by Mike Full along with local friends, family and volunteers. Fossils extracted were restored and preserved by Mike Full with input from various sources, including the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. An agreement was made with Dr. Orr that the fossils would remain in the care of Mike Full, but that the entire fossil collection and records would be public domain, and that the Condon Museum could request ownership at any time (an agreement that continues to this day).

1998 Summer Dig…..The first professional dig Dr. Robsen Bonnicshen, director of the Center for the Study of the First Americans, then located at Oregon State University was contacted and assessed the site for a possible excavation. His team of paleo-archeologists conducted a dig, along with a taxonomic and taphonomic alalysis of the fossils already extracted from the site. Dr. Bonnischen facilitated a radiocarbon dating test of a fragment of the mammoth maxillary bone. Stafford laboratories, Boulder, Colorado conducted collagen dating. The bone was in excellent condition and yielded an XAD-Gelatin date with a 14C Age of >46,400 RCYBP.

Additionally, Dr. Bonnicshen and his team conducted a stratigraphic survey of the site. His findings are explained in detail in the published paper mentioned above. The fossil material is located in a sandy blue clay matrix, overlain by a poorly sorted gravel flood deposit. This in turn is overlain by several meters of sandy-silt flood deposits showing obvious sedimentary layering. The sandy blue clay layer extends down below the water line, to an undetermined depth. It bears not only the fossil remains of the Columbian mammoth, but also scattered remains of bison, at least one other mammoth, rodent and rabbit as well as fresh water mussel and snail fossils. Also in evidence is flora consisting mainly of twigs and small bits of wood, with an occasional limb or small trunk of a tree.

2007 Summer Dig…..Overland access enables the site to be worked vertically, top to bottom During the summer of 2007, Dr. Alison Stenger and her crew from the Institute for Archeological Studies conducted a summer dig on the McMinnville Mammoth Site. While scouting the bottom of the river for fossil bones that had possibly eroded from the mammoth site, a bison femur was found protruding from the bank not far upstream from the McMinniville Mammoth Site. Registration marks and the meter grid system was continued, and the summer dig was expanded to include both the mammoth and bison sites.

The premier find at the Mammoth Site was made by Mark Fitzsimmons of Alison Stenger’s staff: the upper pallet of the mammoth, complete with one molar. This find could be fit with the molar originally found into place, and the left tusk socket found on the first year’s dig also fits perfectly into place. With a small skull plate found years earlier identified as a right orbital, and the right zygomatic arch also found by Mark the same year, it is possible to imagine the skull taking shape before your eyes!

To date, approximately a quarter to a third of the mammoth skeleton has been recovered, consisting of skull parts, three of four molars, the aforementioned left tusk, several ribs and vertebra, both scapula and a femur. The material is in very fine shape, showing little evidence of erosional wear or desiccation and exfoliation. Green bone breaks are common (possibly trampling fractures) as well as gnaw marks from predation and/or scavenging. The gnaw marks are consistent with dire wolf and rodent. Photographs in-situ were taken of specimens recovered at both sites along with GPS coordinates and a paper was produced for the City of McMinnville detailing both finds. This paper is also included in the publications section mentioned above.

Curiously, while many of the smaller bones, such as vertebra, and hundreds of bone fragments have been located, which indicates this is a carcass that was predated and/or scavenged where it died and not subjected to high velocity aquatic dispersal, land slump or other high energy natural occurrence; the heavy and dense upper and lower leg bones have not been fount in-situ. The sole leg bone found, a femur, was fifty yards downstream found worn out of the bank, and can not be conclusively demonstrated to be from this mammoth.

2009 Summer Dig…..Site expansion and careful scientific methodology The 2009 Summer Dig began 08 August, and continued through 23 August. It was conducted by the Institute for Archeological Studies, Instructed by Dr. Alison T. Stenger and Dr. Lyle Hubbard; oversight by Dr. William Orr. The class, conducted through Chemeketa Community College,introduced students to field archeological and paleontological methodology, with an emphasis on practical field work.

The same grid was used as on previously established digs, and with some phenomenal assistance from the local gang, the City of McMinnville, and especially from Waldo Farnham who donated the use of his track hoe and operated it himself; we expanded the available area of the dig by about 300 percent.

Dr. Alison Stenger and Dr. Lyle Hubbard conducted classroom instruction and the crew from the Institute for Archaeological Studies acted as staff and instructors on-site. Dr. Stenger produced the site paper, which is available under “publications” in the User section of the website.

The students had an extremely successful class, and we soon had a bison vertebra emerging from the gravel Bretz flood layer just over the fossil bearing blue clay layer of the site. Once into the site, the right tusk socket of the Columbian Mammoth began to emerge, complete with the right tusk in it.

The right tusk had been broken, during the animal’s life, undoubtedly through normal use and wear, and had been worn down smooth at the stump end through continued use. Another amazing indication of the story that each fossil has to tell!

2012 Summer Digs……Tracks in Time, Possible Pleistocene Mega Fauna Track Discovery The 2012 digs were hampered by unit availability. Much higher than normal early rainfall levels and record summer month river flows made the site inaccessible in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, again due to unusually high water levels, the site was not accessible until late July. Additionally, the South Yamhill River is a very active system and the site was found to be covered with slump and depositional overburden. Equipment brought in to clear off the site became mired and it was impossible to clear off the entire dig site.

Clearing off the site to the limits of the available equipment and by hand resulted in two ends to the dig being opened up, with a substantial amount of slump material left in between, effectively dividing the dig into two different areas. Still, on one end of the dig, an area large enough to view as a whole was excavated to a single level for the first time and the results were startling:

Tracks Discovered! McMinnville High School students participating in a fieldtrip with instructor Cory Eklund and Yamhill River Pleistocene Project volunteer on-site scientist Dr. Lyle Hubbard excavated several contiguous square meter grids. At the end of the second day, the students (now hot and tired) tended to excavate differentially, scooping out softer material and avoiding hardpan. This left a series of “potholes” in the otherwise flat excavation surface. What we had been passing off as random variations in the strata now showed what appears to be uniform size and recognizable patterning, resembling an animal track way. The tracks appeared in size and shape consistent with what one would expect to see in mammoths.

The following weekend, the North American Research Group conducted a scheduled dig at the site and members were briefed as a matter of interest to look for more evidence of the track way as they excavated. More tracks were discovered, these were a bit more carefully developed, out of curiosity. At the conclusion of this dig and after a bit of internet research, the possible tracks were identified as most probably belonging to mammoth. Again, mostly as a matter of curiosity, they were mentioned to the next two groups scheduled to dig the site: a Linfield College class under instructor John Syring and the Institute for Archaeological Studies under Dr. Alison Stenger, also the volunteer on-site scientist for the Yamhill River Pleistocene Project.

Tracks Identified! Dr. Stenger who showed great interest in the possibility of the site containing mega fauna tracks, began developing resources and researching the possibilities. As the scientist in over site, Dr. William Orr was also briefed on the possibility of Pleistocene tracks. Dr. Lyle Hubbard, who had kindly volunteered to act as on-site scientist for the Yamhill River Pleistocene Project also committed to being a resource in the developing investigation.

During the scheduled digs, Dr. Stenger’s group concentrated on developing the suspected animal track way while the Linfield College students excavated adjacent grids down to the fossil bearing layer. These were the last scheduled digs of the summer and scheduled to last only two days.

Dr. Stenger started by adding small amounts of water to each suspected track depression, darkening them to contrast with surrounding matrix. Examinations of the “tracks” showed size, shape and patterning which matches modern elephant track ways and known, confirmed mammoth track ways. The depressions were photographed and a site diagram was started.

At the end of the second day, suspected prints from the previous digs had been cleaned off and dressed for photographing, measurements, sketching and prepared for further development the next weekend when Dr. Hubbard had organized an additional crew consisting of Oregon Museum of Science and Industry volunteers with excavation and casting experience to finalize the preparation of the suspected tracks and produce casts.

The possible mammoth track way coincides with past observations of “soft spots” found while excavating adjacent grids and during the original horizontal digs inside the densest part of the excavated bone bed to date. These possible tracks were not recognized for what they might be and therefore not documented.

Tracks Lost! The OMSI crew arrived to find that the carefully excavated grid squares had become inundated with ground water during the previous week due to the trench channeling ground water away from the grids having failed. The grids were approximately six to eight inches below the water table and thus formed pools which acted to re-hydrate the fossil and track bearing layer which was now unprotected by the over layer of impermeable gravel stone.

The result was to turn the carefully developed top layer of strata, which had once shown suspected mammoth tracks, some showing what appeared to be faint toe detail surrounded by clearly visible pressure ridges, into unrecognizable goo. While the affected area only extended approximately two centimeters into the sediment, it was enough to distort or destroy all of the previous work in developing the fragile tracks and the faint pressure ridges surrounding them. Salvaging useful information would mean carefully cleaning the surface of the dig and excavating what remained of the tracks for depth and bottom details.

Re-Developing the Tracks Work was started immediately to see what could be salvaged from the mess in the two days available for the dig.

Re-developing the tracks consisted of draining the grids and removing material which had flowed into the grids with the water, as well as any remaining overburden of poorly cemented gravel stone ancient riverbed deposit to get to the fossil bearing layer, then carefully working down through the layer of “goo” to expose the differentiations that indicated tracks. The tracks, as expected, are in the fossil bearing layer which tended to consist of sandy silty clay, very compacted and hard to excavate. The suspected tracks appear to be depressions in the surrounding matrix that are filled with a much more uniformly sorted sandy clay that is poorly cemented and more easily excavated, or in some cases filled with silty blue clay, also more easily excavated than the fossil bearing layer.

Careful observation as the excavation progressed appears to show not just the suspected mammoth tracks, but bison, ground sloth and deer as well. The sandy clay still did not hold crisp detail well, side slump and fill in were apparent in nearly every track and many tracks appeared to have been stepped on or in, partially destroying them or rendering them quite equivocal when viewed singularly. When viewed as a whole, some directional tracks are discernible in the limited area exposed, adding credibility to the scenario that we are looking at a late Pleistocene river bank where mega fauna came to water alongside the bones of a Columbian mammoth.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

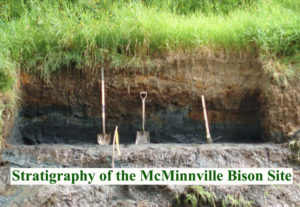

03 McMinnville Bison Site

(Refer to scientific papers located in the “Publications” section of the web site for stratigraphic studies, fossil identifications, taxonomic descriptions, and other information of general scientific interest on this site.)

The McMinnville Bison Site has been excavated over a number of years by the Yamhill River Pleistocene Project. Research at this site is ongoing, and it is closed to the public without specific reason and permission from the City of McMinnville which controls access to the site.

The McMinnville Bison Site was discovered “officially” in 2007, when Mike Full discovered a bison femur sticking out of the eroded bank of sandy blue clay while scouting for the upcoming dig at the Mammoth Site. Its site designation was bestowed by Dr. Alison Stenger of the Institute for Archeological Studies, and it was included in that year’s summer excavation.

We had been locating fossils at this location, just upstream from the McMinnville Mammoth Site and in geologically the same type of strata, for years; protruding out of the same sandy blue clay, overlain with the gravel flood deposit. Mostly, these bones have shown pronounced desiccation, some exfoliation and wear, being not in as good of condition as those of the mammoth. The bison femur was in the same great shape as the mammoth bones, showing gnaw marks on both ends, consistent with a dire wolf.

Previously, the area has yielded freshwater mussel shells, bone fragments, a mammoth and a bison calcaneus, rib fragments from a deer or elk sized animal, and a muskrat nest containing two exquisitely preserved perfectly articulated muskrats, and a small rabbit skull.

2007 Summer Dig: The 2007 dig at the bison site was a modest one, only a few square meters. The partially exposed femur was excavated first. It showed gnaw marks on the femoral head, consistent with a wolf sized predator; and the distal epithesis was missing, apparently due to carnivore gnawing. A cervical vertebra from a bison was uncovered and a few bone fragments, and the site will hopefully yield more in the future.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

04 The Gilpin Creek Fossil Site

(Refer to scientific papers located in the “Publications” section of the web site for stratigraphic studies, fossil identifications, taxonomic descriptions and other information of general scientific interest on this site.)

THE GILPIN FOSSIL SITE IS ENTIRELY ON PRIVATE PROPERTY AND IS NOT OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.

In 2007 Charlie and Max Gilpin, along with their friend Aspen, were playing in the Creek that runs through their property and enters the South Yamhill River just downstream. Their attention was drawn to a strange looking object weathering out of the bank: it turned out to be a large molar from a mammoth. John Gilpin (Charlie and Max’s father) contacted Dr. William Orr of the Condon Museum at the University of Oregon who confirmed the discovery, and notified Mike Full. A site assessment turned up several more bones, including part of a large mammoth scapula, in the log and vegetation clogged stream course.

The Gilpins had a trip to Los Angeles to appear with their fossils on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno. Upon returning, they embarked on a backyard adventure that netted dozens of late Pleistocene fossil bones. Participating with Dr. Stenger, John Gilpin had a piece of mammoth bone radio-carbon dated. The dating came back at 12,800 YBP, making it a very exciting find from the perspective of paleo-archeology. Early human habitation is known to have occurred by then.

With the help of Dr. Orr, and later that of Dr. Alison Stenger and her contacts and resources, several of the bones were found to be diagnostic. In evidence so far are mammoth (Mammuthus columbi), Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlonii), extinct bison and beaver. Closer taxonomic study will undoubtedly confirm further species. John Gilpin is a staunch advocate for the environmentally friendly excavation and study of the fossil site, and has been wonderfully active and helpful in facilitating the scientists.

2008 Summer Dig: With the high density of finds in Gilpin Creek, Dr. Stenger and the crew from the Institute for Archeological Studies conducted the summer 2008 dig at the Gilpin Creek Fossil Site with the permission and amazing cooperation and assistance of John Gilpin. John did a great deal of site preparation, and brought in equipment to establish a road bed down to the site. He and his family furnished a parking area, water, sanitary facilities, and a great deal of participation, support and friendly conversation throughout the summer.

Of great interest was a red jasper Cascade style projectile point found in the stream bed at the fossil site by Mike Full. This was followed up by the even more exciting finds by the Gilpins, locating two Haskett style projectile points in the same location. While no human component has been demonstrated in situ yet, the discovery of the ancient projectile points in close proximity to a fossil bed is indeed exciting.

The summer, 2008 dig was laid out on a meter grid with registration points. The stream bed was thoroughly searched, and the area next to it carefully excavated. Many bone fragments were found in situ, and much further study is needed to determine whether they were initially deposited here, or were washed downstream from some unknown location.

The fossils are undergoing preservation and restoration by Mike Full, and John Gilpin is maintaining care and custody of them, although he has pledged the fossils, ultimately, to the Condon Museum. The grid charted locations on the preserved specimens will be forwarded to Alison Stenger for study and documentation.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

05 The Royer Mastodon Site

(The location of the Royer Mastodon Site is given on the maps located in the “User Pages”. It is located on private property and is not open to the public without permission.)

Melissa Royer Riches presented us with a fossil find from her childhood in 2001 which she had collected along the banks of the South Yamhill River. She related to us that:

“This tusk, believed to be from a woolly mammoth or elephant, was found b Hillsboro resident, Melissa Royer Riches, and a friend, Paul, in June of 1977 on the banks of the north (sic) Yamhill River, a tributary of the Willamette River, near McMinnville. The teen-agers first thought they had tripped over a root, but excavated and were delighted to discover that they had found a fossil. Several years earlier a neighbor had discovered a tooth along these banks. Later in the rainy season of 1979, approximately February, the renter on the Royer property reported having seen vary large bones along the river, but that they had washed downstream by the time he could investigate.”

Melissa was kind enough to take us to the site, which is actually on the South Yamhill River, and pointed out where she remembered the tusk to have been discovered. There has been significant bank movement in the intervening years and a large slump now covers the location. No further in-situ fossils have been recovered from the location.

Sadly, we do not know the name of the neighbor nor where the tooth now resides that was found earlier, since if it could be associated with the tusk, would identify the animal as either mastodon or mammoth. It is listed here as a mastodon as it was tentatively identified as such by Dr. William Orr of the Condon Museum based on general dimensions, proportions and shape.

Also lost is the name of the renter mentioned in Melissa’s narrative, who may have been able to provide a more detailed description of what he saw on the banks of the South Yamhill River.

Each year the site is re-evaluated via a river float and search, sometimes encompassing scuba. A mammoth tooth plate and a partial scapula to a Harlan’s ground sloth have been located downstream on gravel bars, but to date no diagnostically identifiable mastodon material has been found.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

06 The Crimmins Mammoth Site

(This site at present is reported but not researched. The site location is available only to vetted researchers.)

The Crimmins Mammoth is on private property . It is closed to the public without permission from the land owner who controls access to the site.

The Crimmins Mammoth was discovered by Duane Crimmins in the mid to late 1960’s when, as a teen ager, he discovered a mammoth tusk on the family farm. He realized the importance of what he had found eroding from a blue clay matrix along the North Yamhill River and carefully excavated the badly worn tusk. Subsequent visits to the site yielded a partial mammoth molar and fragments of a mammoth tooth which he reported to his McMinnville High School teacher. He has maintained the tusk in a framed shadow box . Both the tusk and the molar that accompanies it are in remarkably stable condition for a non-preserved/restored/stabilized specimen from the type of strata described.

The specimen appears to represent the distal portion of a tusk of unknown original length, but probably not much longer than that collected. It is approximately 1/4 of the tusk in radius, being approximately a four inch arc at its terminus. The tusk is in excess of three feet long tapering to a rather fine point. A tooth plate accompanies the tusk in the shadow box and is consistent with the tusk in condition and permineralization.

Found separate from the tusk and mammoth tooth plate was a mammoth tooth. It is nearly complete, representing perhaps 75 to 80 percent of the original tooth and most probably is a left lower molar. Condition and permineralization are notably different than the tusk and tooth plate and the tooth plate spacing and size are different from the tooth plate found with the tusk, indicating that this find probably represents a different animal.

The Crimmins Mammoth Site has been covered by a large bank slump, so although the exact location of it is know, it is not at present accessible to excavation or study.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

07 Palmer Creek at Dayton, Oregon

(This site at present is reported but not researched. Specific information is available only to vetted researchers.)

Palmer Creek passes through private property . It is closed to the public without permission from land owners who control access to the site.

Palmer Creek is a tributary of the Yamhill River, its mouth being very near the Dayton boat landing. It is named for Oregon Pioneer Joel Palmer, whose house still stands in Dayton, Oregon. The creek has reportedly yielded both mammoth and sloth fossils:

Joel Palmer, himself, discovered mastodon bones in Palmer Creek, as a newspaper article of the day, preserved by the Oregon Historical Society reports:

“Discovery of the Remains of a Mastodon near Dayton. About thirty miles south of this town, near Dayton, some remains of the nipple-tooth or Mastodon have lately been exhumed. They were found by Gen. Joel Palmer, on the west bank of a small stream about three hundred yards from the Yamhill River, at a depth of about 14 feet below the surface.”

The fossils recovered were reported to be two molars still set in bone, one tusk and parts of two others. The intact tusk was described as being about 6 1/2 feet in length and 5 inches in diameter. The article speculates that the fossils were “sent east”, but at this point they seem to have vanished from history.

In 1963, fossils were again found in Palmer Creek. The location appears to be very close to that described by Joel Palmer, and they were reported to be those of a giant ground sloth. No supporting documentation has surfaced to support the discovery, and no photographs have been found which would aid in their identification. The bones were reportedly stored in a local barn, and at this point, bad luck intervened: the 1963 “Columbus Day Storm” destroyed the barn and the fossils were never found. Whether destroyed or stolen, their fate is unknown.

The topography of Palmer Creek is strikingly similar to fossil sites throughout the Willamette Valley, and the possibility of a significant fossil location there is more probable than not.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________________________

This cranial fragment was found along the banks of the Yamhill River, Yamhill County, Oregon. Probably sometime in the late ‘40s/early ‘50s. The name of the finder has been lost as has the exact locus of the find. The cranium was donated to

Linfield College, McMinnville, Oregon through the auspices of Dr. John Boling, Professor of Biology. There were no tags or other notes associated with the cranium. It sat in a glass case in a “room” seldom used for classes.

I first made an acquaintance with the “Linfield Sloth” my freshman year at Linfield College. I was told it was a giant ground sloth found along the Yamhill. For the next four years I walked by it and wondered about it, but did little to dig into the specimen. Finally, my senior year I got Dr. Boling to go looking for the site somewhere along the Yamhill River. We looked but to no avail. He had also forgotten the donor’s name. It had been some time back.

I left Linfield and two days latter was on an oceanographic vessel off Southern California and Baja. For various reasons I never returned, but the sloth was always resence in my mind … haunting.

Upon retiring from the University of Alaska I eventually returned to the Portland area. I went back to Linfield to see my mentor Dr. Jane Claire Dirks- Edmunds. She was largely responsible for my surviving at Linfield. Her Biology curriculum has been my intellectual foundation. I did not see the sloth at that time. Dr. Edmunds assured me it was still in its case, largely ignored.

After Dr. Edmunds died I re-connected with the Biology Department through the auspices of my association working archaeological sites along the Yamhill River. I asked about the sloth and it was produced. At last I was face-to-face with my tormentor. Tormentor? Yes! It never left my head and I frequently mentioned it in conversations with folks. I needed to know it!

Mike Full (Willamette Valley Pleistocene Project founder) and I took it to his “Trophy Room” where, along with two live rattlesnakes, he had been cleaning and preserving numerous Pleistocene fossils for decades. Now I had it in hand and was determined to wring information out of it. We determined (with Greg MacDonald’s expertise) it was an Harlan’s Ground Sloth- Paramylodon harlini (or is it Mylodon harlini?)! There are those that claim it to be the former while others the latter. Bottom line: It is a “small” ground sloth!

THE DETAILS:

- It is a pretty good neurocranium with anterior elements (orbits and nasals) missing

- It has no teeth and only 3 or 4 molar sockets sockets.

- Surprisingly, it has survived its discovery (after at least 12, 000 years) while lying sodden in water logged sediments. Then it was discovered, cleaned and dried out! We do not know how much damage was done to the cranium in that process. No notes of discovery are known to exist.

- We named it: The Linfield Sloth.

- We have done a full metric analysis under the expert guidance of Dr. Greg Macdonald.

- We hope to make a cast of the fossil as time allows.

- Upon completion of our assessments, and casting, we will return the Linfield Sloth to the Linfield College Biology Department.

SOME DETAILS RE HARLAN’S GROUND SLOTH:

- Sloths belong to the same taxonomic group (Order Xenarthra= xenos : strange and arthros : joint) as anteaters, armadillos and other sloth forms- extinct and living.

- They apparently arose in South America and migrated north finally crossing the Isthmus of Panama when (before?) that land passage became available early in the Pliocene. On reaching North America these pioneers diversified. Some became as large as rhinos, more than 10 feet long, while Harlan’s Sloth was merely the size of an ox- approximately 6 feet long, standing about 3-4 feet at the back..

- Early in the 19th Century Thomas Jefferson came into possession of a sloth.

He named it Harlan’s Sloth. It was given a Latin name in keeping with biological protocols: Mylodon harlini– Harlan’s sloth. Subsequently, as in somewhat common in taxonomy (scientific classification) the name was

changed to Paramylodon harlini. Both names are used as not everyone buys into the changes, but M. harlini seems to prevail.

- Sloths are found across North America; from Virginia to California. They

are plant eaters (herbivores). It is assumed that they ate small shrubs and dug roots with their immense foreleg claws. However, in the La Brea tar (Los Angeles) and the Desert West scat has been found containing Mormon Tea (Ephedra) and Mallow (Sphaeralcea). They ate what was available!

- Skeletal features:

- Skull: Large, elongate and with a blunt nose.

- Stout hind limbs that indicate they were able to haunch-sit in a semi-erect mode while browsing.

- They possessed stout, large forelimbs with strong claws on digits II, III and IV. Their claws probably were used to strip leaves off trees, dig roots and tear small bushes out by their roots. A ponderous browser (grazer) lifestyle may be affair characterization?

- They were covered with thick red hair and had robust tails.

- Most peculiarly, however, their skin was possessed of “dermal ossicles” (boney, octagonal shaped platelet armour).

- One would think with stout tails, strong, clawed forelimbs and dermal armour they would be a formidable opponent for carnivores!

- TEETH:

1) They had 16(18) teeth; no incisors, canines or premolars.

2) They had a 5/4 dental formula; 5 maxillary molars over 4 mandibular molars. It appears that the 1st max. molar may have been incisiform (chisel-like) perhaps used in clipping

plants off at their stems/branches. However, some of the sloths apparently did not have these incisiform molars resulting in a 4/4 dental formula (an unresolved issue).

3) Teeth were deep rooted: 6” or more in length.

- They all became extinct by ca, 11, 000 bp.

- Coincides, roughly with the end of the last glacial age.

- They have been found associated with the tools of Homo sapiens.

- Perhaps, the beginning of the on-going, human caused, “Sixth Extinction”.