Yamhill Rivers Mega Fauna

Whether washed out or in situ the most fascinating finds have to be the fossils which turn out to be taxonomically diagnostic. We are fortunate enough to be able to call upon the expertise and skills of Dr. William Orr, curator of the Condon Museum of Natural History at the University of Oregon in assisting with the identification of fossil fauna. His mentoring of us over the past many years has been an invaluable asset to our endeavors.

The sedimentary deposits also contain the scattered and shattered remains of victims of flood events as well as the exquisitely preserved and relatively undisturbed remains of local fauna. Two separate locations have yielded mammoth remains that have been radiocarbon dated at 12,800 YBP and greater than 51,700 YBP respectively, making the finds significant not only to the paleontologist, but also the paleo-archeologist.

While some species such as mammoth and mastodon have many bones that are strikingly similar; others such as the giant ground sloth, seem singularly strange and unfamiliar. As a general rule, the teeth are the most taxonomically significant of the bones, and a single tooth can definitively confirm a species.

Our fossil collection confirms, through teeth and taxonomically diagnostic bones, the presence in our area of study eight varieties of megafauna: mammoth, mastodon, sloth, bison, horse and camelid.

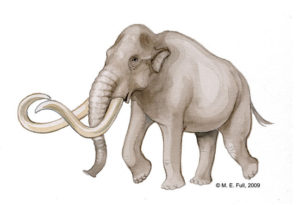

Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi)

Columbian Mammoth (Mammuthus columbi)

Mammoth fossils are some of the most common we encounter, for two very simple reasons: first, they were apparently fairly common, and second, their large size makes their fossil remains easier to see and harder to destroy. Mammoth are known to have gone through several sets of teeth in their lifetime, and our collection represents several distinct sizes, from infant (YR 598) to adult (YR 001) .

The Columbian mammoth were grazers, undoubtedly herd animals, larger than the more famous woolly mammoth or modern African elephant which is its closest living relative. Adults could stand almost four meters tall and weigh nearly ten metric tons. Tusks on an adult bull could be four and a half meters in length.

Colombian mammoth appeared in North America in the late Pleistocene, and are believed to have become extinct approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, with isolated populations lingering well into the Holocene. We have been fortunate enough to have radio-carbon dating done on two of our specimens: the Gilpin Site mammoth gave a radio-carbon date of 12,800 ybp and the McMinnville Site mammoth at in excess of 51,700 ybp.

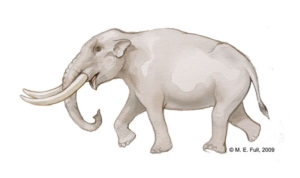

American Mastodon (Mammut americanum)

American Mastodon (Mammut americanum)

Taxonomically diagnostic mastodon fossils are much more scarce than mammoth, although many of the largest fossil bone fragments could in fact belong to either. Only two mastodon teeth have been found to date. One (YR 012) is probably shed from a sub-adult to make room for the next tooth and showing a great deal of use related wear: the other (YR 348) is a very small tooth, split longitudinally, from an infant Mastodon.

Several bones identified as Mastodon have been located in what appears to be a fossil debris fan not far upstream from the McMinnville Mammoth Site, but the location of the in situ remains has not been located.

The Royer Fossil Site has yielded a huge tusk fragment (YR 345) in situ back in the early 1970’s which has tentatively been identified by Dr. Orr as Mastodon, as well as a complete rib (YR 317).

The American mastodon stood nearly three meters at the shoulder, about the same size as the woolly mammoth. They are generally believed to have become extinct at the end of the last ice age, approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, although recent radio-carbon dating indicates some may have survived a few thousand years into the holocene.

The mastodon was apparently far less common in our area than the mammoth; possibly because as a browser that did not live in herds, it tended to forage in the foothills among the forests, away from the flat grasslands bordering the ancient Yamhill River watershed.

Giant Ground Sloth (Paramylodon harlani)

Giant Ground Sloth (Paramylodon harlani)

(Refer also to the article “The Linfield Sloth” by Dr. Lyle Hubbard, PhD., below)

The giant ground sloth evolved in South America and migrated north. Of the several genus of sloth that were found in North America, the Harlan’s Ground Sloth is the commonest in our area. It was an enormous beast, and at two meters tall and weighing nearly 4000 kilograms, it neared the size of a small modern day elephant.

The giant ground sloth were another victim of the extinction occurring at the end of the last ice age, generally presumed to have gone extinct in North American some 12,000 years ago. The humerus of a Harlan’s Ground Sloth from our study yielded a radio carbon date of 16,620 years before present.

The flat grinding teeth of this huge beast indicate a diet of grasses, but probably also included twigs and leaves obtained and held in front paws equipped with giant claws. With its primitive peg-like teeth with the unique “figure 8” grinding surface, dermal ossicles, overly stout broad and deformed looking leg bones, compressed feet and ankles and huge claws; everything about Harlan’s Ground Sloth looks strange and out of place.

The number of sloth fossil found along the Yamhill Rivers is probably indicative of three factors: They were not uncommon in the area, the robustness of the animal yielded heavy, robust bones that perhaps were less likely to be destroyed before preservation, and the sloth was so dissimilar to every other megafauna that diagnostically it is often very easy to identify. A tooth (YR 339), a partial scapula (YR 271), two sloth digits (YR 148, YR 238), some vertebra (YR 101, YR 166, YR 38.016), and a rib (YR 197) are among the fossil remains of Harlan’s ground sloth, but the most striking sloth fossil off the South Yamhill River is the Linfield College sloth cranium, found by a McMinnville resident in the 1960’s.

Along with mammoth remains, the bones of extinct bison are the most common fossil specimens we have discovered. Like the mammoth, the bison was a grazer and a herd animal, likely grazing up and down the Willamette Valley for millennia. Their fossilized remains litter the Pleistocene sediments and commonly show up wherever erosion has brought them to the surface. Larger than our present day bison, some species had a horn spread of over two meters. Near the end of the Pleistocene, the extinct bison was abundant in our area, probably holding on into the early Holocene.

Fossilized horn cores both partial and complete have been retrieved from the South Yamhill River and are diagnostic to bison species. The river has yielded specimens identified as both Bison antiquus (YR 259, YR 370, YR 406) and Bison alaskensis (YR 260, YR 464).

Bison teeth are, next to deer, the commonest teeth we find on the Yamhill Rivers. Their robust leg bones are also common, as well as vertebra, and we have recovered three complete horn core and pieces of others, as well as partial mandibles of bison, some still containing teeth of this ancestor of our modern buffalo.

Along the Yamhill Rivers, bison fossils have been found in situ at both the Gilpin Fossil Site, and the McMinnville Mammoth and Bison Sites. Some of these fossils show distinct evidence of predation or scavenging, in the form of gnaw marks consistent with wolf-sized predators.

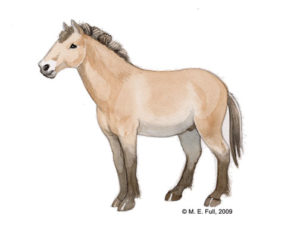

The horse originated in North America, evolving into its final form, genus equus, before becoming extinct from the end of the last ice age until reintroduced by the Spanish during the “conquest” of the new world.

The horse has a particularly well studied fossil record, with new species having been designated by the subtle nuances of the dental grinding patterns. We have recovered several complete teeth and fragments of extinct horse, but lacking the expertise of the experts in the field we will classify them as “genus equus” while making the observation that we have two distinct Pleistocene horse species.

We have several fossils indicating an equine of present day horse size, including several teeth, the distal end of a tibia, a lumbar vertebra and three well ossified metacarpal. While this constitutes a very small data pool, it does suggest horses as we would recognize them today were a common sight in the late Pleistocene Willamette Valley.

In contrast to that, two fossils indicate a separate population of smaller equines: a small, yet well ossified distal epythesis of a horse cannon bone as well as a small tooth showing a distinctly simpler grinding surface pattern, suggest that we had at least vastly different sized adults, if not different species, in our area. Because of obvious differences observed in the grinding pattern of the equus tooth, it that was sent to the Page Museum for identification. This tooth was subsequently identified as from an ass or onanger.

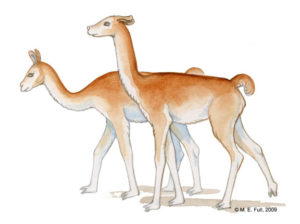

Camelids – The Giant Ice Age Camel (Camelops hesternus) & The Large Headed Llama (Hemiauchenia macrocephala)

Camelids – The Giant Ice Age Camel (Camelops hesternus) & The Large Headed Llama (Hemiauchenia macrocephala)

Camelids (camels and llamas) evolved and diversified in North America. Ancestors of today’s modern camel migrated across the Bering Land Bridge to the old world. Others migrated south across the Panamanian Land Bridge to South America, evolving into llamas, guanacos, alpacas, and vicunas that we see today. Subsequently, the entire family died out in North America at the end of the last ice age.

Hemiauchenia macrocephala: After going for years after we found it without an identification, the Page Museum at the La Brea Tar Pits was able to identify for us a tooth (YR 049) as belonging to an extinct camelid, Hemiauchenia macrocephala the large headed llama. The small tooth was identified as a fetal tooth showing no wear to indicate the young animal had ever used it. This single tooth is, to date, our only identified fossil of this animal.

Hemiauchenia macrocephala, the large headed llama, is a late Pleistocene llama that stood nearly two meters high at the shoulders. It’s skeletal remains show it to be very long and slender, and it was probably a mixed browser and grazer. To date, we know of no other remains of this animal found west of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon.

Camelops hesternus: During the summer of 2012, a tooth (YR 265) was collected which was tentatively identified as a bison molar. Due to subtle differences between it and other teeth which were known bison molars, it was shown to Dr. Christopher Shaw, PhD of the Page Museum, who was able to identify it as Camelops hesternus. It is the only positively diagnostic fossil of this animal that we have found to date.

Giant Ice Age Beaver (Castoroides)

Giant Ice Age Beaver (Castoroides)

The most elusive megafauna documented so far has been Castoroides, the Giant Ice Age Beaver. Castoroides was the largest of all beavers and grew to the size of a small black bear, weighing in at perhaps as much as 125 Kg (276 pounds) and as long as 2.2 meters (7.2 feet). Well adapted to water, with its eyes and nasal openings set high on the skull, Castoroides was undoubtedly semi-aquatic, though no evidence to indicate that it built dams or lodges has been found.

Never before documented with provenance west of the Continental Divide, Dr. William Orr PhD speculated in the 1980’s that the environmental conditions of the Willamette Valley in the late Pleistocene were excellent for the giant beaver, and there was no reason that it should not be found here….the hunt was on!

In 2017 a partial incisor (YR 433) diagnostic to Castoroides, was collected on a point bar of the South Yamhill River. Positively identified by Dr. William Orr, PhD, it was then reported to Dr. Gregory McDonald PhD. Subsequently, Dr. McDonald identified a humerus (YR 201)which had been collected and tentatively identified as Castor in 2010 as being Castoroides.

On May 15th, 2021 another Castoroides fossil was collected from the same gravel point bar that yielded the first two specimens. This one, (YR 627) consists of a partial left mandible containing a broken incisor and four molars embedded in a poorly sorted sand and gravel cemented together by the thick sandy blue clay common in the area dating to the late Pleistocene. Still in the process of having the surrounding matrix removed, the specimen further confirms the occurrence of this species in the Willamette Valley.

The grey wolf was perhaps the commonest apex predator of the late Pleistocene. Fossils from other sites in North America indicate that the grey wolf and its larger cousin, the dire wolf, coexisted during the late Pleistocene. The dire wolf became extinct, the grey wolf survived into modern times, and indeed is re-populating Oregon at present.

Fossil remains of this carnivore consist of a skull recovered from late Pleistocene – early Holocene deposits. Discovered eroding from the bank of a small creek draining into the South Yamhill River in 1997, it was at first assumed to be the skull of a very large dog, until identified as grey wolf by Dr. William Orr, PhD.

While this is the only positively diagnostic fossil from this animal that we have found to date, we have found other evidence indicating that the wolf was a common apex predator in our area: The McMinnville Mammoth Site has yielded a cranial fragment, the right superorbital, which has damage identified by Dr. Robsen Bonnischen, PhD; as wolf scavenge or predation. At the nearby McMinnville Bison Site, a bison femur was recovered which has very clear gnawing marks on both epenthesis consistent with canine type activity. Comparing these marks to the carnassial teeth of wolf dentition shows a very favorable and compelling match.