King’s Valley Site

Kings Valley Sloth Site

Dr. William N. Orr, PhD.

Because of land owner cooperation, site accessibility, a high safety factor and generous community cooperation this fossil site dig was one of the easiest and most productive of my career. Kings Valley landowner, Ted Leonard was excavating a natural spring on his land when he began to turn up a variety of large and small fossil bones. Dr. Bill Bonnischen, an archaeologist, originally dug at the site (dated at about 12,000 years before the present) some years earlier in a quest for human remains. After a series of unfortunate political maneuvers he was driven off the site by his own institution, Oregon State University. A consequence of this was his move to a university in Texas. Ted Leonard contacted me some years later as director of the U. of O. Condon Museum and I was delighted to initiate a dig for fossil mammals on the site.

Because of land owner cooperation, site accessibility, a high safety factor and generous community cooperation this fossil site dig was one of the easiest and most productive of my career. Kings Valley landowner, Ted Leonard was excavating a natural spring on his land when he began to turn up a variety of large and small fossil bones. Dr. Bill Bonnischen, an archaeologist, originally dug at the site (dated at about 12,000 years before the present) some years earlier in a quest for human remains. After a series of unfortunate political maneuvers he was driven off the site by his own institution, Oregon State University. A consequence of this was his move to a university in Texas. Ted Leonard contacted me some years later as director of the U. of O. Condon Museum and I was delighted to initiate a dig for fossil mammals on the site.

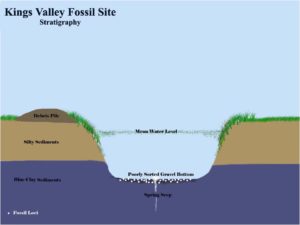

The site accessibility is near optimum in the middle of an agricultural field where an ancient natural freshwater spring has created a low knoll, about two feet high and several tens of feet in diameter. Parking was easy and accessibility to the site with heavy machinery was both safe and convenient.

The team of upwards of 40 souls to perform the dig was remarkably diverse including geologists, paleontologists, students from a local college, interested local neighbors and even several enthusiastic grade school-aged children. What made the setting a dream site was the high safety factor, easy accessibility of fossils and array of tasks that volunteers could choose from. This site produced sloth bones from the very beginning as well as several other large and small mammals. Because prehistoric sloths are armored with a thick, horny “coat of mail” skin studded by small bony fragments (dermal ossicles), a sieving operation was initiated to recover these tiny but critical pieces. Using water pumps and a stock tank as many as six or eight individuals including youngsters were able to participate in sieving operations. This means that everybody had the opportunity to find and uncover and handle fossils of several descriptions. At the other end of the operation several volunteers were tasked with taking notes and photographically recording finds while two to three individuals were mucking out fossil bearing muds from the bottom of an eight foot pit. Bone material at the site is especially well preserved and as whole bones and fragments were unearthed they were washed, evaluated and almost invariably identified on the spot by the site paleontologist. Volunteers were then able to see first hand the direct result of their labors. The creature recovered to give the site its name was Mylodon harlani (the Harlan groundsloth). Reaching up to nine feet high and weighing almost three quarters of a ton these animals were solitary vegetarians ranging all over North America during the ice ages and only disappeared about 11,000 years ago due to hunting pressure by early americans. Because all operations on the site were readily visible and above ground, the safety factor was near optimum. Volunteers were able to switch around tasks and assume different roles at will and the work proceeded at a brisk pace. The dig was performed in three successive years in late summer, early fall after agricultural operations ended for that year. The Condon Museum greatly benefitted by acquiring a large suite of Pleistocene (ice age) sloth bones and other mammals that included a rich array from juvenile to adult specimens.

tasked with taking notes and photographically recording finds while two to three individuals were mucking out fossil bearing muds from the bottom of an eight foot pit. Bone material at the site is especially well preserved and as whole bones and fragments were unearthed they were washed, evaluated and almost invariably identified on the spot by the site paleontologist. Volunteers were then able to see first hand the direct result of their labors. The creature recovered to give the site its name was Mylodon harlani (the Harlan groundsloth). Reaching up to nine feet high and weighing almost three quarters of a ton these animals were solitary vegetarians ranging all over North America during the ice ages and only disappeared about 11,000 years ago due to hunting pressure by early americans. Because all operations on the site were readily visible and above ground, the safety factor was near optimum. Volunteers were able to switch around tasks and assume different roles at will and the work proceeded at a brisk pace. The dig was performed in three successive years in late summer, early fall after agricultural operations ended for that year. The Condon Museum greatly benefitted by acquiring a large suite of Pleistocene (ice age) sloth bones and other mammals that included a rich array from juvenile to adult specimens.

Local media came to the site and produced a definitive news article with pictures of all manner of volunteers working.

It is truly exceptional to be able to allow volunteers in this way to actively participate in a safe manner and the Kings Valley local community got behind the operation in a friendly and cooperative manner only occasionally enjoyed in these endeavors.